The American mind has a particular soft spot for the general category we label as "Nature." Walk through the aisles of any grocery store as evidence. Muted pastel color pallets of greens and browns, faux burlap graphic texturing, distressed typefaces that appear hand stamped, a litany of promises, slogans and certifications. The message is clear- that the natural, or at least the appearance of it, is always synonymous with the good. There's even a "natural" version of Cheetos available for the more discriminating junk foodies among us. In short, we've become rather sentimental, but it's not all our fault.

Some argue that our notions of the natural are bound up with our romantic ideas about the untamed wilderness, or the American frontier, a recent chapter in our collective story. One might also point to the influential "boosters" of the 20th century conservation movement- Muir, Thoreau, Mcharg and others. Beyond merely exalting the virtues of spending time outside in nature, these early boosters contributed to a powerful and pervasive narrative of loss that colors our perspective of what nature is and more importantly, what it isn't.

As fields, forests and pastures gave rapid rise to highways, factories and tenements, development came to represent the opposite of Nature. “Nature” now reduced to an idea, represented an antidote to the ills and constraints of civilized life. But the more our cities sprawled, the less untouched wilderness we felt we had left. And our responses took on a remedial tone. Over the past century we've created National Parks and native plant societies, formed committees and drafted laws, and generally expended lots of energy and resources attempting to emulate the pre-human, pre-urban ecologies of the past. Even the front lawn, another revered American invention, reflects a collective desire to define and care for little pristine domestic wildernesses of our own. As long as we can manage to keep the dog shit and dandelions at bay.

European attitudes toward nature differ in both concept and application. After centuries of agricultural development, wars, and layers upon layers of city building, the notion of pristine wilderness is a much more distant memory. This is to say that notions of the natural have always been intertwined (rather than at odds) with human activity. Nature exists not only to the extent that it has been left alone or restored to an arbitrary historical baseline, but because it has been curated, augmented, tended to over time. Take as an extreme example, the entire country of Holland. A place without a past to return to. Through a series of strategic dykes, levees, and other feats of regional hydro-engineering, the Dutch have reclaimed territory from the sea and thrived for hundreds of years. From the surreally vibrant Tulip fields of Anna Paulowna, to the managed wildness of the Oostvaardersplassen, these “designed” ecologies represent a unique framework for development that is simultaneously 100 percent natural, and 100 percent artificial.

Exploring this contrast in thinking from a historical and cultural perspective is not to say that one way of thinking is inherently right, but to emphasize that our ideas about Nature matter. They always inform our actions. Sometimes they inform our inaction. Next week, we’ll explore what’s at stake and what’s possible as we shift from a sentimental to a more instrumental view of Nature, and what it means for the future of our cities.

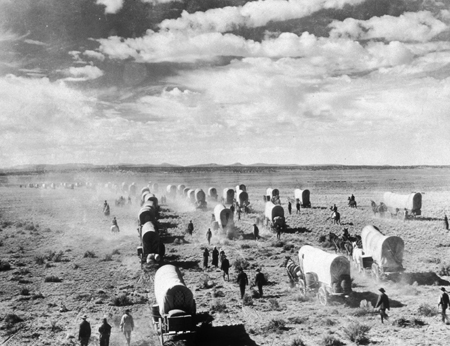

PHOTO: Normann Szkop / Rex Features